Cerebellum Obscura

For as long as I can remember, karaoke is the place I’ve felt most myself. When I’m onstage, I’m one with the music, the moment, the crowd. I shimmer. I flow. Until one night, I didn’t.

In spring 2024, I had a stroke. My worst fear was losing a part of my thinking brain — a part of me. But I got lucky. Doctors told me the stroke was in my cerebellum, a thoroughly “non-essential” part of the brain whose job was to help me move smoothly through space. After a blow to the cerebellum, they told me, you might feel a little clumsy. But you’ll still be you.

Reassuring, right?

Over the next few months, a lot came back. But there were also these weird, inexplicable glitches.

We all have an idea in our heads of how we move through the world, our patterns of talking and walking and thinking. Suddenly, I didn’t know how anything was going to come out. I’d plan a sentence I wanted to say, then mix up the words. I’d think “your” and then type “you’re” (an unforgiveable sin, for a writer). I’d send the command, but once it left my brain, the message seemed to scramble on its way to the real world.

Karaoke became the place I feared the most. Every night, I hoped something would go differently. I’d choose a song I’d performed hundreds of times. Visualize myself singing it. Get on stage. Then I’d stand stiffly, woodenly, as the notes spilled out in the wrong key, at the wrong tempo.

I felt like a puppet whose strings had been cut.

So I came to Radiolab to solve a medical mystery. I wanted to know why, if this part of my brain was so unimportant, I no longer felt like me. I was a science journalist, after all. The Mz. Frizzle of the vagina (so I’ve been told). I thought I could do for the cerebellum what I did for the clitoris: Trace back the biases and blind spots that blocked science from appreciating a part of the body that was central to the human experience.

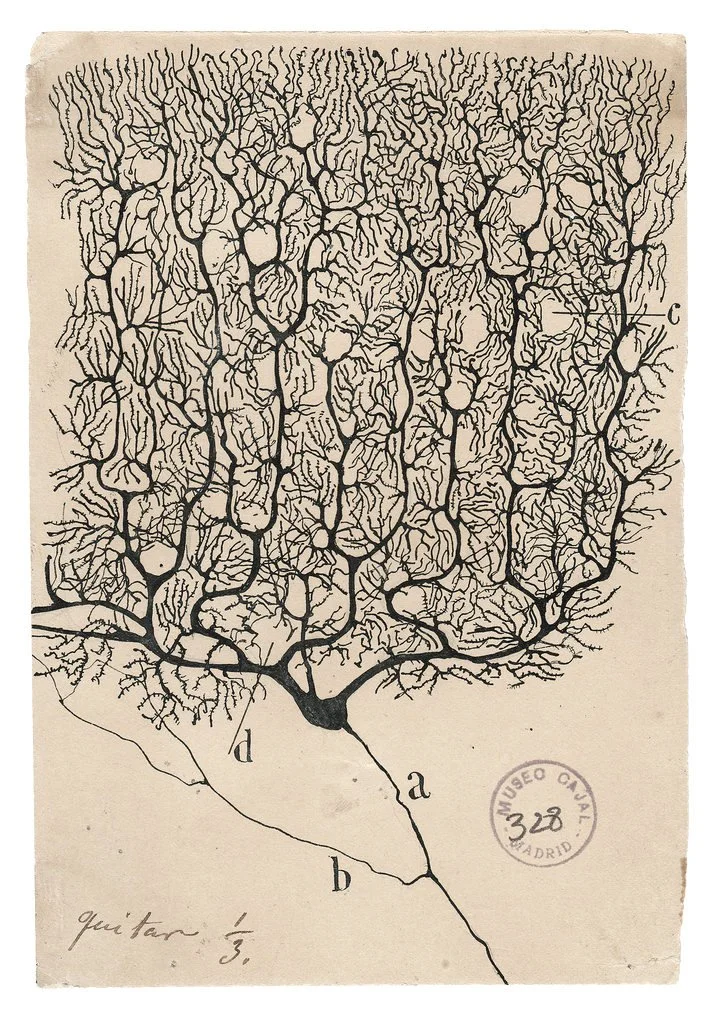

Sketch of a Purkinje neuron of the human cerebellum, by Ramón y Cajal.

And that’s kind of what I did. With Radiolab producer Sindhu Gnanasambandan, I learned that the cerebellum was once the jewel of neuroscience. It was where Santiago Ramón y Cajal, the father of modern neuroscience, first discovered the treelike creature known as the neuron. Cajal praised the cerebellum for its elegance and crystalline structure, its rows of outstretched cells branching into infinity.

But by the 1900s, a peculiar logic had come to color the way we think of the brain. It was a belief, popularized by phrenologist Franz Joseph Gall, that those regions that were lower down — as in, literally, lower in space — must be involved in “lower” functions. They simply did the basic tasks all animals do to survive: regulating heart rate, blood flow, breathing.

The cerebellum, by that logic, was one of the lowliest structures of them all. It would become known as the body’s conductor. Its purpose, scientists thought, was to smooth out your movements, so that when you went to shoot a three-pointer, hug a friend, or pirouette across a dance floor, the action unfolded naturally, seamlessly, without you having to think about it.

Important? Sure. But to neuroscience, not all that exciting.

As a result, for decades, the cerebellum has been largely overlooked. Even today, researchers often crop it out of studies (seriously!), or leave it out of brain atlases. (The brain’s clitoris, amirite?) Here’s the problem: While its name means “little brain,” the cerebellum is actually packed with four times as many neurons as the rest of the brain.

All those crackling communication centers can’t just be helping you move. Right?

For this story, we tracked down the scientists starting to ask: What if we’ve gotten the cerebellum all wrong? What if the reason this fist-sized chunk o’ brain is so dense, so swole, so foldy, is because it’s actually orchestrating something far more vital to who we are than just our movements?

Karaokeing, post-stroke, with writer Jaime Lowe.

The problem is, understanding what you’ve lost doesn’t make the ache disappear. In the end I was left with a question science couldn’t answer: When you lose a part of yourself, can you grow a new ‘you’ around the wound? Is the self a language we can relearn?

This is a story about coming to appreciate an invisible part of all of us, a part that allows our bodies and thoughts to unspool effortlessly, across time and space. It’s a story about finding beauty in a self that is a little messier, a little less polished, than the one we were taught to accept.

It’s a story about losing your voice, and finding a new one.

I hope it makes you think. I hope it makes you dance.

Thank you for listening.

- Rachel